Metadata, data documentation, and provenance

Better Code, Better Science: Chapter 7, Part 8

This is a possible section from the open-source living textbook Better Code, Better Science, which is being released in sections on Substack. The entire book can be accessed here and the Github repository is here. This material is released under CC-BY-NC.

Metadata

Metadata refers to “data about data”, and generally is meant to contain the information that is needed to interpret a dataset. In principle, someone who obtains a dataset should be able to understand and reuse the data using only the metadata provided alongside the dataset. There are many different types of metadata that might be associated with a study, and it is usually necessary to decide how comprehensive to be in providing detailed metadata. This will often rely upon the scientific expertise and judgment of the researcher, to determine which particular metadata would be essential for others to usefully interpret and reuse the data.

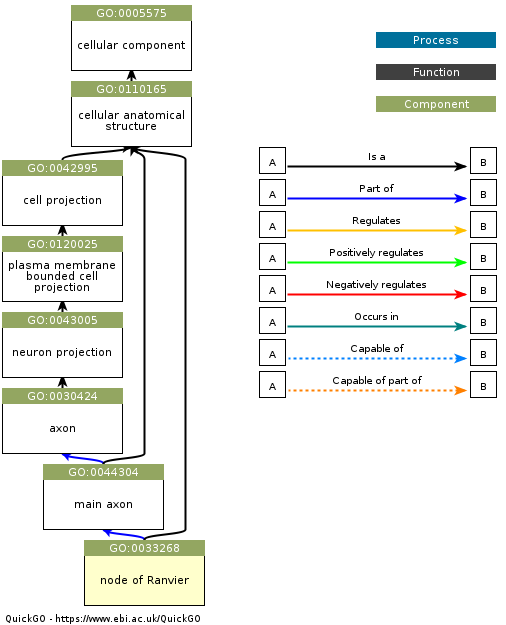

An important concept in metadata is the ontology. In the context of bioinformatics, an ontology is a structured representation of the entities that exist in a domain (defined by a controlled vocabulary) and the relationships between these entities. One of the best known examples in the Gene Ontology, which represents classes of biological entities including Molecular Functions, Cellular Components, and Biological Processes. As an example, this figure shows a Gene Ontology graph for the entity “node of Ranvier”, which is a component of a neuron (obtained from here).

Ontologies are very useful for specifying metadata, because they allow us to know exactly what a particular entry in the metadata means, and thus allow us to establish link between equivalent entities across datasets. For example, let’s say that a researcher wants to query a database for datasets related to insulin signaling in pancreatic beta cells in Type II diabetes, and that there are three relevant datasets in the database. Without an ontology, each of the teams might use different terms to refer to these cells (such as “pancreatic beta cells”, “insulin-producing cells”, and “islet beta cells”), making it difficult to link the datasets. However, if each of the datasets were to include metadata linked to a specific ontology (in this case, the identifier CL:0000169 from the Cell Ontology, which refers to “type B pancreatic cell”), then it becomes much easier to find and link these datasets. There are at present a broad range of ontologies available for nearly every scientific domain; the BioPortal project provides a tool to search across a wide range of existing ontologies.

Metadata file formats

An important feature of metadata is that it needs to be machine-readable, meaning that it is provided in a structured format that be automatically parsed by a computer. Common formats are Extensible Markup Language (XML) and JavaScript Object Notation (JSON). JSON is generally simpler and more human-readable, but it doesn’t natively provide the ability to define attributes for particular entries (such as the units of measurement) or link to ontologies. An extension of JSON known as JSON-LD (JSON for Linked Data) provides support for the latter, by allowing links to controlled vocabularies.

For example, let’s say that I wanted to represent information about an author (myself) in JSON, which I might do like this:

{

“name”: “Russell Poldrack”,

“affiliation”: “Stanford University”,

“email”: “russpold@stanford.edu”

}Now let’s say that someone else wanted to search across datasets to find researchers from Stanford University. They would have no way of knowing that I used the term “affiliation” as opposed to “organization”, “institution”, or other terms. We could instead represent this using JSON-LD, which is more verbose but allows us to link to a vocabulary (in this case schema.org) that defines these entities by providing a @context tag:

{

“@context”: “https://schema.org”,

“@type”: “Person”,

“name”: “Russell Poldrack”,

“affiliation”: {

“@type”: “Organization”,

“name”: “Stanford University”

},

“email”: “russpold@stanford.edu”

}Data documentation

While metadata is generally meant to be used by computers, it is also important to provide human-readable documentation for a dataset, so that other researchers (or one’s own self in the future) can understand and reuse the data successfully. There are two forms of documentation that can be important to provide.

Data dictionaries

A data dictionary provides information about each of the variables in a dataset. These are meant to be human readable, though it can often be useful to share them in a machine-readable format (such as JSON) so that they can also be used in programmatic ways. A data dictionary includes information such as:

an understandable description of the variable

the data type (e.g. string, integer, Boolean)

the allowable range of values

For example, a study of immune system function in human participants might include the following in its data dictionary:

| Variable Name | Data Type | Allowable Values | Description |

|---------------|-----------|------------------|-------------|

| age | Integer | 0-120 | Age of the participant in years |

| gender | String | M, W, O | Participant’s self-identified gender |

| crp | Numeric | 0.1-50.0, -90, -98, -99| C-reactive protein level (mg/L) |Codebooks

A codebook is meant to be a more human-friendly description of the content of the dataset, focusing on how the data were collected and coded. It often includes a detailed description of each variable that is meant to help understand and interpret the data. For the example above, the codebook might include the following:

Variable Information

Variable name: crp

Variable label: High-sensitivity C-reactive protein

Variable definition: A quantitative measure of C-reactive protein in blood serum.

Measurement and Coding

Data Type: Numeric (Floating Point, 2 decimal places)

Units of Measurement: mg/L (milligrams per Liter)

Measurement Method: Immunoturbidimetric assay.

Instrument: Roche Cobas c702 clinical chemistry analyzer.

Allowable Range: 0.10 - 50.00

Note: The lower limit of detection for this assay is 0.10 mg/L.

Values and Codes:

[Numerical Value]: A continuous value from 0.10 to 50.00 represents the measured concentration in mg/L.

-90: Value below the lower limit of detection (< 0.10 mg/L).

-98: Unusable sample (e.g., sample was hemolyzed, insufficient quantity).

-99: Missing (e.g., sample not collected, participant refused blood draw).

Collection Protocol and Provenance

Specimen Type: Serum from a venous blood sample.

Collection Procedure: Blood was drawn from the antecubital vein into a serum separator tube (SST) after an 8-hour overnight fast. The sample was allowed to clot for 30 minutes, then centrifuged at 1,500 x g for 15 minutes. Serum was aliquoted and stored at -80°C until analysis.

Date of Creation: 2025-11-15

Version: 1.0

It is essential to generate data dictionaries and codebooks upon the generation of the dataset; otherwise important details may be lost.

Provenance

Provenance refers to particular metadata regarding the history of processes and inputs that give rise to a particular file. Tracking of provenance is essential to ensure that one knows exactly how a particular file was created. This includes:

the origin of original data (such as the instrument used to collect it, or date of collection)

the specific input files that went into creation of the file, for files that are derived data

the specific versions of any software tools that were used to create the file

the specific settings used for the software tools

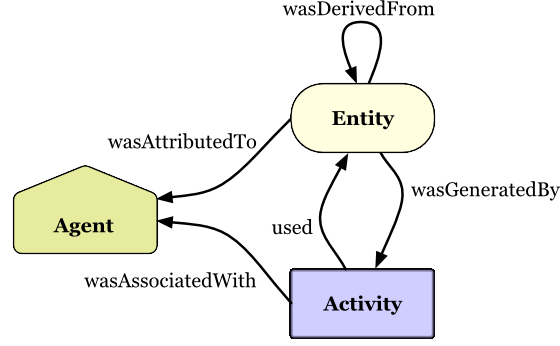

Tracking of provenance is non-trivial. The World Wide Web Consortium (W3C) has developed a framework called PROV which defines a model for the representation of provenance information. This framework provides an overview of the many features of provenance that one might want to record for an information that is shared online. The PROV data models defines three main concepts:

Entities: things that are produced, such as datasets and publications

Activities: processes that involve using, generating, or modifying entities

Agents: People, organizations, or artifacts (such as computers) that are responsible for activities

In addition, the model defines a set of relationships between these concepts, as shown in this figure from the W3C:

(Copyright © [2013] [World Wide Web Consortium]).

This data model highlights the breadth of information that needs to be represented in order to accurately record provenance.

There are several different ways to track provenance in practice, which vary in their complexity, comprehensiveness, and ease of use. We will discuss this in much more detail in a later chapter on workflows.

In the next post I will discuss the handling of sensitive data.